Lessons

Lessons From The Riding School

Cressmount

The riding school I attended as a young person flourished at Mills College in Oakland, California. It consisted of a school horse barn, a boarders’ barn, a clubhouse, an indoor arena the size of a large dressage court, a huge show ring with grandstands, the Upson Downs hunt course and glorious eucalyptus trails interlacing the campus. There was always good fun at Cressmount, reflecting Miss Cress’s love of the horses and her keen sense of humor. What a heavenly place to grow up with horses!

The 16 well-trained show-quality horses, each had their own character and style. They were well-kept and immaculately groomed. All the tack – 16 saddles and 32 bridles – were cleaned every Saturday afternoon. (I know because I cleaned tack for riding lessons.)

The 16 well-trained show-quality horses, each had their own character and style. They were well-kept and immaculately groomed. All the tack – 16 saddles and 32 bridles – were cleaned every Saturday afternoon. (I know because I cleaned tack for riding lessons.)

I learned to ride in group lessons. The horses knew their jobs, but they were no pushovers. Being social animals, the horses enjoyed the group riding. Along with two great instructors, they taught us to find our balance and learn the aids. The arena riding featured lots of patterns that taught us to apply the aids correctly. The variety of horses gave us a wide range of experience. Clubs and competitions and camaraderie fostered manners and good sportsmanship.

The school was created and run by Cornelia Van Ness Cress, the daughter of a US Cavalry general. She grew up and learned everything about horses in that disciplined world. She brought all that with her to the school, including balanced riding. As she put it, “We follow the pattern of our Military School of Equitation, accepting the military balanced seat, which allows maximum control by rider with minimum strain to horse and rider. Briefly, this is a deep, firm seat, allowing the more erect position for pleasure riding and dressage and the forward seat for fast riding over cross country jumps and uneven terrain.”

Then and Now

Riding schools have a long history through the centuries, rooted in the military tradition. When I think about it, in order to go into battle, horsemen needed to be comfortable in the saddle to ride countless miles. They needed to have their mounts under control, but at the same time, give them the freedom to navigate difficult terrain and to move quickly and efficiently, as needed. As a result, the horses were able to give their best to their riders – mutual trust and respect between rider and horse were paramount. There was no time on the battlefield to get into an argument with your horse.

At the Spanish Riding School, descended from the royal court, students – to this day – begin their education on the longe line. There, they ride without reins for months on end in order to develop a strong, steady seat before they ride on their own.

Today, many people do not have the benefits of a good riding school. Horse lovers are left to their own devices when acquiring horses – some that are not suited to them, be it age, soundness, temperament, experience or degree of training.

Teaching is challenging. As Forrest Gump put it, “Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.”

Lessons From The Horses

We all know that the horse is the largest domesticated animal. He’s a social creature. Generally, horses prefer the path of least resistance. Of course, there is an occasional exception. In pasture, they find their places in their hierarchy quickly. They respond well to consistency and predictability. These are clues as to why they are so trainable. When we look at the spectrum of different disciplines, methods and purposes for which horses are trained, we can see that it is their good nature that makes it all possible. However, regardless of their fate, horses always tell the truth.

If we are observant, we can learn the horse’s language and can successfully communicate. This is a mental and physical body language. Our developing a mutual understanding with the horse on the ground is foundational to riding. However, a good relationship with the horse on the ground doesn’t necessarily translate into success in the saddle.

Observing the horse in motion, we can see how he shifts his balance. Once mounted, a rider is immediately challenged to balance. This is the beginning of balanced riding. If the rider can follow the horse’s movement, then the rider can positively influence it. As riders, it is our job to discover how we can stay in balance in this dynamic activity.

Center of Balance

The illustration identifies the approximate location of the horse’s center of balance. Of course, it is not on the outside of the horse, but internal and central. We can see that the horse’s weight is distributed over its haunches and forehand. Because of the heavy head and neck, he carries the greater amount of weight on the forehand. As the horse changes gait and speed, the head and neck adjust upward or downward, accordingly.

It is no coincidence that when we sit on the horse for riding, we sit very close to this center of balance. We can communicate with the horse through our own center of balance and weight.

The Crooked Horse

The Crooked Horse

We need to observe the horse while standing (see top view) and in movement. All horses naturally travel crooked. There are many theories as to why they are this way. It makes most sense to me that they are born crooked, very likely due to the way they were positioned in the womb. Whatever the reason, this fact must be taken into account when riding.

We speak of the stiff side and the hollow side. In reality, the horse is stiff on both sides. However, when you look at the horse, you will see that one side appears hollow. So, for purposes of explanation, I will use these two terms. On the stiff side, the horse will carry more of its weight than on the hollow side. Often, we will see a bulging, overdeveloped shoulder on the stiff side. Watching the horse move will help us identify the stiff side and the hollow side. Moving in the direction of the stiff side, the horse will look to the outside and will appear to drop its shoulder inward. In contrast, moving in the direction of the hollow side, the horse will look to the inside. In balanced riding, information about the crooked horse is critical to our understanding.

Footfalls Matter

An important way to get to know the horse – both from the ground and from the saddle – is to observe the rhythms of the walk, trot, canter and back. We discover that the horse naturally has a four-beat walk, a two-beat trot and a three-beat canter, as well as a two-beat back. (Of course, this is true of most horses, but there are exceptions, for example, horses bred to pace.) The rhythms of the gaits are the foundation for the simplest, most efficient way for the rider to communicate with the horse. Through his rhythms, the horse tells the rider precisely when the rider’s aids are most effective – actual moments in time.

Riding is a living art. This information about the horse’s center of balance and way of going is key to riding successfully. For more detail, read Checks & Balances: Teaching the Half-Halt and Conversations with Riders.

Lessons From Horses I Have Known

My First Ride

My enjoyment of horses began when I was seven. I sat for hours on the pasture fence behind our house, watching the horses milling around and munching grass. Used to seeing me there, they became nosey. I’d pet them and talk to them, certain they knew what I was saying. One day a wide-backed one sauntered up beside me. I just slid onto his back from the fence. He shot across the field, and I hung on to his long mane for dear life! As he reached the far fence and stopped short, the whole thing was over in a flash. I remember looking up at him as he stared back at me with a shocked look on his face. Days and weeks went by, and I tried it again. This time he stood there, consenting to my being on his back. That’s how it started.

Sage Cock

I rode Sage Cock cross-country in my late teens. He was a high spirited, athletic, well-trained chestnut Thoroughbred. Junior, as he was called at home, was one of the school horses ridden by intermediate and advanced riders only. I think I got to ride him because I was a quiet rider. If I pointed him in the right direction, he usually took care of the rest.

One time I was riding Junior over a two-mile course. This was the only time I experienced getting my second wind. Good thing I did. As we approached the last fence, he swerved to the left and left me in the dirt. When I stood up, I still had the reins in my hand – and the bridle intact. He took off with such force that the bridle slipped off his head (testimony to well-conditioned leather). He hightailed it to the staging area where other horses were awaiting their turn on the course. That was that. Because Junior had a habit of taking charge, a cowboy tried to change his mind, but to no avail. It was quite a rodeo.

Chantilly

This Quarter Horse mare was an elegant bay. I was attracted to her looks and kind manner. She was trained Western. Somehow, she became the first horse that I actually owned. With my upbringing with horses, I thought I could retrain her to go the way I knew how to ride. Here is an example of acquiring an unsuitable horse for me. While she was very sweet and willing, she couldn’t make the switch. I was not an experienced trainer. The combination didn’t work. I found a good home for her with a Western rider.

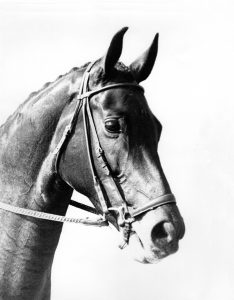

Document

This 17-hand bay Thoroughbred was trained to Grand Prix Dressage by celebrated trainer and Olympic coach, Erich Bubbel. Document was owned by Susan Davidge. I knew Susan through our association with the California Dressage Society in the 60s and 70s. Susan generously lent Document to me for several months. This was the opportunity of a lifetime for me. I learned a great deal about classical dressage from him. I, being a lightweight 5’6” tall rider, felt very small up on Document. However, thanks to balanced riding, he kindly accommodated me.

Chappo

Here was a large pony that became a junior champion endurance horse. He was trained and conditioned to travel long distances. After many successes, and as he aged, he started to show slight lameness in his right hind at the trot. The rider did not want to hurt the horse, but she wanted to keep competing. So, she began riding him in walk. Chappo evolved into a very fast walker. He showed no lameness in walk. She shortened her competitive rides from 100 miles to 25 miles, and this team went on to more wins for a couple of more years.

When Chappo was retired, I acquired him. I found a large pasture with other horses, where he lived out his life to age 32. I never rode him. However, his original owner warned me that if I did ride him and he started farting, it meant he was ready to start bucking. Chappo never took lightly to being roughed up.

Chappo and I became good friends, as I fed him his grain and groomed him every day. That was our time together. As my grandkids grew big enough, Chappo became their ride. They were completely sweet with him, and Chappo played along joyfully.

Farra Viva

Farra was my perfect horse. She came to me in a dream and manifested one day when we were seeing each other for the first time. Unbeknownst to me, she would become my riding horse after a lifetime spent looking for her – at a time that I could no longer afford a horse of my own. Ray graciously invited me to ride her. From then on, she was mine, at least in my heart.

Farra, a soft chestnut, was Crabbet Arabian. She was just right for my size. Her gaits were smooth as silk, and she always did exactly what I asked of her. I called her My Cadillac. She always stood still when I mounted and dismounted. We would go through our paces – collected, medium and extended walk, trot, canter, flying changes, half-pass. Then we’d go on a long walk over the hills. Heaven.

For stories of Scatterall, Duffel Bag, Gypsy and other horses I have known

read Spirit Horses of Periwinkel and Valentine and Other Magnificent Ponies

Lessons From The Teachers

My Beginnings

I grew up in a riding school patterned after the Military School of Equitation. This is a comprehensive, yet simple method that stands on the shoulders of long-standing traditions of horsemanship, dating back to Xenophon – an example of the old saying, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

My first riding teacher, Cornelia Van Ness Cress, was raised on a US Cavalry base, where she learned every aspect of horsemanship. She taught respect. As she put it, “A horse is the only partner who never lets you down.” It was in this atmosphere that I learned to ride. For a full account of her life, Read More.

Every day Miss Cress dressed in riding clothes, complete with immaculate boots and riding jacket. She required all students to arrive dressed to ride – jodhpurs or breeches, high boots, jodhpur boots or oxford shoes with low heels, white shirt and hunt cap. (This was before the invention of the helmet.) Good manners were always in order. The schedule was strict. We had to show up at least a few minutes before our lesson began or we didn’t ride. The group lessons were fun, often accompanied with lively music by John Philip Souza. Instruction was to the group as a whole with tips to individual riders as needed. Each group represented a particular level of riding – beginner, intermediate, etc. The advanced group rode first to settle the horses into their day – sometimes up to four lessons.

All of the horses were of show quality, most of them jumpers, so there were jumping lessons in the arena as well as cross country. Trail riding was also included.

Because the school was so large and demanding, Miss Cress employed her protégé, Gia Abel, to take on some of the classes. Gia was also instrumental in my progress. Here is a picture of me on the Upson Downs cross-country course. I was riding El Saltador that day in 1957 on our way to winning The Triway. Gia, serving as Show Steward, is standing by. Sal has his eye and ear on the camera.

When I graduated from high school, I left riding behind, and it wasn’t till years later that I came back to it. I found it difficult to duplicate what I experienced at the riding school, and began searching for teachers to help me get going again. This is what I found.

Atherton Dressage

In the sixties a phenomenon was taking place on the grounds of Kyra Downton’s home in Atherton, California. Col. Alois Podhasky, retired director of The Spanish Riding School, was in residence, helping Kyra prepare her Grand Prix horse, Kadett, for the upcoming Mexico City Olympics. Typical of her generosity, Kyra opened her home to Sunday competition/clinics for local riders. I was privileged to attend with my horse, Justice. We would ride a dressage test and then receive personal critique and instruction from the presiding judges – including Col. Podhasky, Hans Moёller and many other prominent European professionals living in the area – professionals who were brought up in traditional military schools – professionals who beautifully conveyed their instruction and corrections. This experience resonated with me, as it brought back my own upbringing.

Horse Trainers

As I watched horse trainers at work, I would look for something that resembled what I knew as a child. When I thought I found that, I enlisted that trainer to be my teacher. Quite often, I found that while the trainer could get results from the horse, he could not convey to me what he was doing. So, his instruction was vague. When I wouldn’t respond accordingly, this would lead to frustration, often with the teacher yelling at me.

I don’t blame the trainer. It’s one thing to ride a horse. It’s an entirely separate thing to be able to explain what you’re doing when you ride. Riders, who naturally ride in balance and naturally develop rapport with the horse, often don’t even realize what they’re doing. As a result, they are far from being able to convey what they are doing and even farther away from diagnosing a student’s needs for progress.

In these situations, I found it most helpful to watch the trainer teach riders who are mounted on horses he has personally trained. The proof is in the pudding. Overall, I did not find professional trainers to be the best teachers for me.

My Standards

We, as teachers, set the standard for our students. For me, this role is extremely important. How I present myself provides the student with a model. I am a formal person. I come dressed in clean riding clothes, my hair neat. If I am in charge of preparing the horse for the lesson, he is well groomed, and his tack is clean and well fitted. In addition, I provide a lesson space with good lighting and good footing. These considerations are based on respect for the teacher, for the horse and for the student. In turn, they provide the student with a baseline for what is acceptable.

Teaching Beginners

To one degree or another, we all learn by doing. In the case of beginners, for sure this is how they learn. So, a beginner must be in the optimum, safe situation to learn by doing. This may require time on the longe line, learning balance and body aids, as the Spanish Riding School taught. Of course, this requires a willing, relaxed horse, trained to longe with a rider.

When the beginner is ready to ride independently in an enclosed arena, sometimes it’s helpful to have a more experienced rider/horse team to act as leader. This arrangement serves two purposes: first, it gives the beginner a chance to ride around the arena without focusing solely on navigating the horse, and second, it provides a role model for the beginner.

Patterns are helpful to acquire balance and correct use of aids. Transitions from halt to walk and back to halt, and then proceeding to incorporate the other gaits, turns on center line, circles, serpentines through a series of cones – all of these exercises and more give the rider challenges and opportunities to experience the horse’s change in balance when moving from left to right and back again and to learn to communicate with the horse accordingly.

Lessons From The Students

Brain Injury

A lady in her 40s arrives with her older gelding, Blaze. She has ridden off and on since she was a young girl. I ask her to take a few minutes to warm up. I suggest she incorporate some transitions and change of direction. This gives me time to evaluate this horse/rider combination. I notice her laboring to post in the trot. To the left, the team looks more balanced and regular in the gaits than to the right. Moving to the right, I see the rider’s inside arm moving around, seemingly disconnected from her body. I am happy to see that the horse is free-moving, easy-going and willing to go along with his rider. He is a good partner for me to provide a learning experience for his rider.

After a short time, I ask the rider to stop her horse and chat. She tells me that she had a brain injury a year ago, that she is well into her recovery and that she is using her riding as therapy. This is very good information for me. Maybe I can help here. After I explain how to stop the horse without pulling on the reins and give her some pointers about her balance , we proceed with practicing on a large circle. In this case, the arena is 15m wide by 30m long, so I spend some time getting her oriented to the circle I want – round, touching the center point on the short side, two specific points on the other sides of the arena she will use as markers, and X, the center point of the arena, which I mark with a cone.

On the circle, we practice stopping the horse without pulling on the reins in walk to halt, and then walk to trot to walk to halt. As we practice, I focus on rearranging her position to bring her seat more forward in the saddle. The exercise of stopping the horse with the body aids goes hand-in-hand with the rider tuning her balance into the horse’s center of balance. As with all horses, Blaze took to this approach – a great boon for the rider to fairly quickly get it.

Practice in both directions helps me zero in on the rider’s right arm, which seems to have a mind of its own – wandering around. As with most horses, Blaze favored tracking to the left, due to his natural crookedness. So, in this direction, the rider appeared balanced and steady. However, in the rising phase of the posting trot, her right arm would fly up dramatically. Tracking to the right, Blaze was especially disturbed with this flying arm, compensating by weaving.

I was perplexed by this puzzle. In the past, to teach steady hands, I would tell the rider to touch the tips of the thumbs together. This came to me as a possible solution here. And it worked better than I ever imagined. The rider immediately became steady and organized in her position, and her right arm stopped wandering. She even exclaimed, “This is working!” After going along for a little while in both directions, I asked her to walk Blaze on a long rein. As they went along, she told me that when she put her thumbs together, it felt like her electric circuits were connected. That made sense, as she reminded me of her brain injury.

What It’s All About

A young teenage girl arrives with her cross-country mare, Glory. It had been a few months since we had worked together. In our previous lessons, this pair performed beautifully, ready to proceed with advanced challenges. I began by asking her what she had been doing. She told me she had been traveling and this lesson was the first opportunity she had to ride since returning from her trip. We continued with the warm-up, and I started giving her instruction, mostly, to encourage her horse to move forward with more energy.

I thought things were going along fairly well, when at one point she stopped. I asked her to keep her horse moving, but as I looked closer, I saw that she was in tears. She seemed frozen in the saddle. She was so upset that she couldn’t talk. I stood by Glory’s head, put my hand on the rein and coaxed her to walk. We started moving slowly forward, and finally the girl opened up and told me she was so happy to see her horse after her long absence that she couldn’t contain herself.

Of course, I realized at that moment that the lesson was over, that I had been interfering with their reunion. So, I suggested that she spend time with her horse. I backed off and watched Glory take her on a long, relaxed walk around the arena, finally stopping in the center – the girl hanging on her neck, hugging her and talking to her. What a splendid moment! It came flooding back to me – what this whole thing is all about.

The Family

I was teaching in a riding school. A family of three cheerful girls and their mother showed up. The girls all wanted to ride. Mom wanted to watch. After a tacking up lesson, I got the girls mounted on school horses, all reliable mounts for inexperienced riders. One of the horses was a good leader, so I got him going and had the others follow behind. The first lesson was in walk. The girls were all relaxed and followed my instructions to go with the horse. My approach was to get the group going as a unit with simple patterns. The horses were used to these patterns, so they were willing to go along with me. This arrangement gave me the tools to teach the girls how to stop their horses without pulling on the reins, to walk them forward and to turn them left and right. By the end of the lesson, the girls were swinging along laughing and thrilled at their progress. They came back for many more lessons, and they progressed to trot and canter and a wide variety of patterns. In addition, they exchanged horses to broaden their experience. This is a success story and testimony to group riding. The girls learned by watching each other. They enjoyed the camaraderie. They fell in love with the horses. In addition, the horses in the arena together provided opportunities beyond what’s available for one rider with one horse.

Emotional Block

A middle-aged lady came to me for lessons. As I watched her walk into the barn, I noticed her hunched back and slung-forward hips. This alarmed me. As I suspected, she carried this poor posture to her riding. She was mounted on Sally, an old-timer used to packing beginners. I started slowly, in the halt, using my hand on her back to encourage her to bring her shoulders back and widen her chest. Proceeding to walk, I encouraged her to feel the horse moving under her and to go with his rhythm as I walked alongside them. As time progressed, she was able to trot the horse and post along on the left circle. After a short warm-up, I asked her to walk the horse and give it a long rein.

For whatever reason, she started talking to me about her troubles growing up and her difficult relationship with her mother. It dawned on me that her experience with the horse had unleashed some old memories that were plaguing her.

As we proceeded with the lesson, I asked her to go right on a circle around me. Something unusual happened. Sally stopped and would not move forward. I knew this horse and realized she was confused by what the rider was trying to ask her to do. I walked up to the rider’s right side and asked her to close her eyes. I put my hand on her knee and asked her if she felt it. She said, “No.” This tipped me off that she had no feeling in her right leg. So, when I had asked her to move forward to the right, Sally had not felt any leg pressure from the rider’s right leg.

As a rider, I experienced riding under instruction, the teacher telling me to put my right shoulder back, and me sending messages to my right shoulder to go back, getting no result. Later in life, I uncovered deep-seated emotional issues that were blocking my body from responding to directions from my brain. Once I eliminated those emotional issues, my body began to respond positively to my direction. I sensed that this may have been happening to this rider. I stopped the lesson and suggested she take the horse on a walk around the arena. I kept my eyes on her as she spent the rest of her time riding around talking to Sally. Ending the lesson on a good note works wonders for the success of future riding.

After the lesson, I suggested enlisting professional help to address her debilitating emotional issues. Interestingly, she did. Several months later, she came back for lessons, and behold, she had developed feeling in her right side.

Blind Sight

The mother of a 13-year-old blind boy approached me about teaching her son to ride. She explained that no one else was willing to take him on as a student. I said, “Yes.” I had no idea what to expect. I enlisted the help of Trouper, a Steady-Eddie gelding with only one forward-going speed in trot. I had the pick of several arenas at this very large riding establishment and chose the little arena – enclosed with white board fence. Trouper knew the arena well. I skipped the tacking up lesson and went directly to getting the boy mounted. He listened attentively to my instruction as I placed his hands on the horse’s neck and introduced him to Trouper. Then on to the saddle. Once mounted, he immediately and miraculously came into balance with Trouper. (Take note!) From the near side, I led him around the arena. As he got his bearings, I stepped slightly away from the horse and told him to close his hand on the right rein if the horse started to move toward me. He did that and was on his way along the fence line. He had a big smile on his face. By the end of the first lesson, he was able to walk, halt and trot on the rail in both directions. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Over the next year, we worked together to achieve amazing results. By that time, he had mastered the arena, changing directions in walk, trot and canter (changing leads through the trot). And he was navigating a simple course of four jumps. In addition, I led him on long walks on the track that ran around the outside cross-country course – his favorite way to cool out after his arena lessons.

Then he and his family moved to the East Coast. A few years later, I was reading The Chronicle of The Horse and came across an article about him riding with The Hunt. I sent back a letter to the editor about my experience with him, who by that time was 18 years old.

These stories of students provide insight into the need for the teacher to be creative and flexible.

Lessons From The Patterns

Riding in patterns has many benefits. It helps the rider relax and get her mind off herself and her horse. Horses learn through anticipation. So, repetitive patterns can provide a way to relax the horse and give the rider opportunities to practice navigating. Patterns can also provide tools for the rider to slow down a rushing horse, to correctly ride the corners of a rectangular riding space, to teach transitions from one gait to another and from one canter lead to the other. Patterns are teaching tools. In group riding, patterns provide a fun way for riders to practice directing their horses.

The circle has been called the perfect pattern. I find blessings and a curse with the circle. It is not easy to ride a perfect circle. However, that is the goal, as anything less contributes to evasions by the horse and weakness of the rider.

In order to determine the circle in our riding space, we must first know its dimensions. Dressage courts are measured to provide an optimum area to ride perfect geometric shapes. However, any riding area can be measured and used appropriately to achieve the same results. It is helpful to have markers on the fence line to guide the rider into a round circle. The best circle size for schooling is 20m. However, if the area is 15m wide, that will work as well. Any smaller than that is for horses advanced in their schooling and athletic ability.

It is helpful for the teacher to start by walking the circle with the student following behind to experience where the circle goes and what it feels like to ride it. One way to describe it is to ride the circle in four separate quarters. With markers, the student can think of it as point-to-point. The more it’s practiced, the rounder it gets.

At first, practicing transitions from walk to halt to walk to trot to walk, etc. in both directions is a good way to get the student going. This exercise highlights the horse’s natural crookedness and specific areas where improvement is needed. It also puts a light on one of the horse’s favorite pastimes – to lean out on the side closest to the exit and to fall in toward the center on the opposite side.

Moving on to more advanced uses of the circle, spirals in and out in trot and in canter provide good gymnastic exercises. For a long time in the development of both horse and rider, just spiraling in one or two meters off the large circle – depending on its size – is sufficient. This is a suppling exercise, providing the rider with practice in body control and weighting the seat bones accurately. It is revealing to discover how little it takes in the seat to move the horse left or right. This exercise is a good introduction to leg yielding as well. The variety of exercises that can be accomplished on the circle is endless, leading all the way to pirouette in canter.

It is prudent to vary the activity often, offering free walk on a loose or floating rein off the circle – to refresh horse and rider. The curse of the circle is that it can be boring. Horses don’t take kindly to being drilled on anything.

A variation on the circle is the pattern called Canter Springs (see 101 Arena Exercises for Horse & Rider, by Cherry Hill – Exercise 40). Even though it is called Canter Springs, it can be done in trot or canter. This exercise requires that the horse and rider have mastered the circle.

Here is an example of how this pattern can be helpful. The horse was balanced and rhythmic on the circle. However, when the rider took him off the circle onto the long side of the arena, the horse rushed. I sensed that the change in balance from the circle to the straight line was contributing to his rushing. I asked the rider to ride a circle the full width of the arena at one end, then continue on the long side for three strides and form a new circle the same size, and upon completion of that circle, continue down the long side for three strides and repeat the circle and so on to the other end of the arena. This is an exercise for the rider to practice being in charge and in balance. It also helps the horse learn that he can maintain a constant rhythm in his stride on the straight line as well as on the circle. To advance the exercise, the number of strides on the straight line between circles can be increased to the point that the pair can maintain the balance and rhythm all the way down the long side. Success may take multiple lessons over time, as this exercise requires both physical conditioning and mental focus of horse and rider. It is important to keep this exercise brief, not to drill the horse in it. Short practice sessions, separated by free walks off the pattern, are most productive.

Lessons From The Literature

For The Horses & Their Lovers, by Diana Mead, dianamead.com

The Pony Club Manual of Horsemanship, any edition

101 Arena Exercises for Horse & Rider, by Cherry Hill

101 Ground Training Exercises for Every Horse & Handler, by Cherry Hill

The Art of Horsemanship, by Xenophon

Cavalletti, by Reiner Klimke

¦